The Art of Calligraphy: A Window into Different Writing Systems and Cultures.

The Art of Calligraphy: A Window into Different Writing Systems and Cultures.

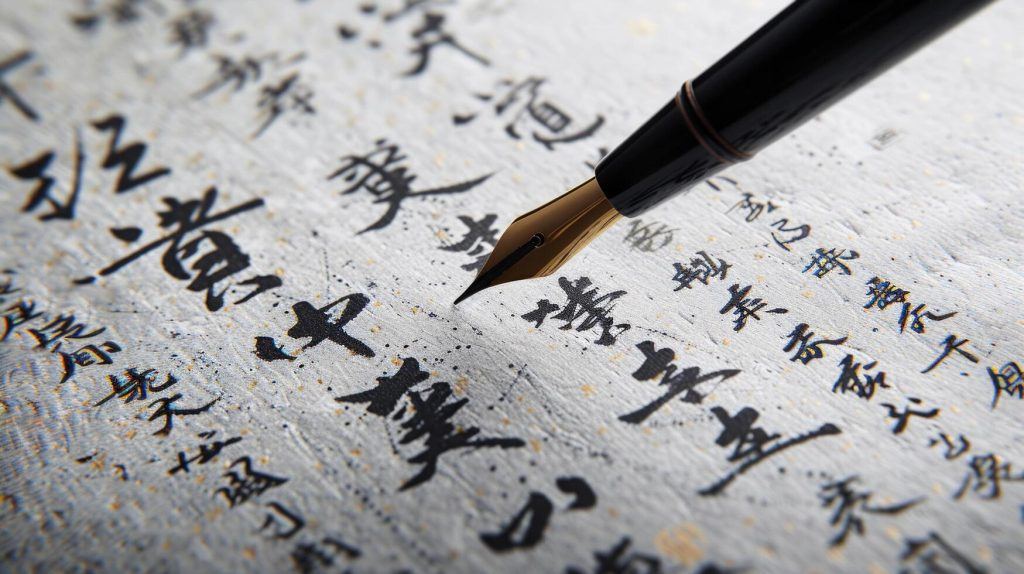

In an age dominated by keyboards and touchscreens, the art of calligraphy stands as a timeless expression of beauty, language, and identity. More than just decorative handwriting, calligraphy is a cultural artifact—a visual form of communication that bridges language with aesthetics. Across centuries and civilizations, from the flowing brushstrokes of Chinese characters to the angular precision of Arabic script, calligraphy has been revered not only as a means of writing but as a deeply spiritual and artistic practice.

This blog explores how calligraphy offers a unique lens into diverse writing systems and cultures, uncovering its role in history, religion, artistic expression, and cultural identity across the world.

Understanding Calligraphy: More Than Beautiful Writing

Calligraphy, from the Greek kallos (beauty) and graphein (to write), literally means “beautiful writing.” However, its purpose extends beyond mere appearance. In many cultures, calligraphy reflects philosophical principles, spiritual beliefs, and social values. It often requires years of disciplined study, involving strict techniques and deep cultural immersion.

Different writing systems have influenced the development of regional styles of calligraphy. Unlike printed fonts, calligraphy captures the rhythm, movement, and personality of the writer. Every stroke is intentional, often revealing deeper meanings that go beyond words.

Chinese Calligraphy: Harmony and Discipline

One of the oldest and most respected forms of calligraphy is found in China, where it is regarded as one of the “Four Arts” of the scholar (alongside painting, music, and the board game Go). Rooted in thousands of years of tradition, Chinese calligraphy (shufa) is not only a visual art but also a form of meditation and philosophy.

Key Features

- Brush and Ink: The brush is flexible and responsive, allowing for dynamic expression. Ink is ground from an ink stick on an inkstone, requiring patience and ritual.

- Character Structure: Chinese characters are composed of radicals and strokes, each placed in a precise order and position.

- Styles: Major script styles include Seal Script (ancient and pictorial), Clerical Script, Regular Script, Running Script, and Grass Script (cursive and expressive).

Cultural Significance

Chinese calligraphy is often associated with Confucian values such as discipline, order, and balance. Taoist and Buddhist influences emphasize spontaneity and natural flow. Masterpieces are displayed like paintings and considered reflections of the artist’s inner self.

Arabic Calligraphy: The Sacred Art of the Word

In the Islamic world, Arabic calligraphy (khatt) holds a special place, especially because of its association with the Qur’an, Islam’s holy book. Since figurative representation was historically discouraged in Islamic art, calligraphy became the primary medium of artistic expression.

Key Features

- Script Forms: There are several styles including Kufic (geometric and ancient), Naskh (legible and formal), Thuluth (ornate and monumental), and Diwani (elegant and decorative).

- Tools: Traditionally, a qalam (reed pen) is used with black ink on parchment or paper.

- Geometry and Symmetry: Arabic calligraphy emphasizes balance, proportion, and flowing curves.

Spiritual Meaning

Arabic calligraphy is not just about beauty—it conveys the divine. Artists often inscribe verses from the Qur’an, prayers, or poetry, blending the sacred with the visual. The act of writing becomes a spiritual exercise, connecting the scribe with the divine through rhythm and repetition.

Japanese Calligraphy: The Way of Writing

Known as shodō, or “the way of writing,” Japanese calligraphy draws from Chinese roots but evolved into its own spiritual and aesthetic discipline. Like martial arts and tea ceremony, shodō is considered a do (path or way), emphasizing mindfulness, form, and flow.

Key Features

- Kanji and Kana: Japanese calligraphy combines Chinese characters (kanji) with native syllabaries (hiragana and katakana).

- Minimalism: Often stark and bold, with an emphasis on simplicity and empty space (ma).

- One-Stroke Flow: The brush should move with fluidity and intention, embodying the Zen ideal of being present in the moment.

Zen Influence

Shodō is closely tied to Zen Buddhism, where the process of writing becomes a meditative act. A single stroke is believed to reveal the spirit and energy (ki) of the writer. Unlike Western calligraphy, perfection is not the goal—authenticity and expression are.

Western Calligraphy: From Manuscripts to Modern Revival

Western calligraphy has its roots in the Roman alphabet, evolving through religious, literary, and decorative traditions. In medieval Europe, calligraphy flourished in monasteries, where scribes meticulously created illuminated manuscripts like the Book of Kells and the Gutenberg Bible.

Historical Styles

- Uncial and Carolingian: Rounded, legible scripts used in early Christian texts.

- Gothic or Blackletter: Dense, angular script associated with medieval Europe.

- Italic and Copperplate: Elegant, flowing styles developed during the Renaissance and Baroque periods for letters and documents.

Tools and Materials

Western calligraphy traditionally uses a dip pen or quill, ink, and vellum or parchment. Modern calligraphers often use fountain pens or brush pens.

Modern Revival

In recent decades, calligraphy has seen a resurgence through hand lettering, typography, wedding design, and art journals. Online communities and workshops have brought new life to this ancient craft, blending old techniques with contemporary styles.

South Asian Calligraphy: Scripts of Diversity

South Asia boasts a rich calligraphic heritage, particularly within Islamic and Hindu traditions. From the elegant Persian-influenced scripts of Mughal India to the decorative Sanskrit inscriptions in temples, calligraphy in South Asia is both devotional and decorative.

Scripts and Styles

- Perso-Arabic Scripts: Used in Urdu and Persian texts, often integrated into architecture and textiles.

- Devanagari Script: Used for Sanskrit and Hindi, though less traditionally stylized, recent revivals have adapted it for artistic expression.

- Grantha and Tamil Scripts: Ancient scripts used in palm-leaf manuscripts in southern India.

Calligraphy in this region often reflects a fusion of cultures—Islamic, Hindu, Persian, and European—making it a dynamic and evolving form of visual communication.

Calligraphy as Cultural Preservation

As digital communication becomes dominant, traditional calligraphy plays an important role in preserving linguistic heritage and cultural identity. Many ancient scripts are no longer widely used in daily life, but calligraphy helps keep them alive.

For example:

- Tibetan calligraphy preserves Buddhist scripture and mantra-writing practices.

- Mongolian script calligraphy is part of UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list.

- Ethiopian Ge’ez calligraphy reflects one of the world’s oldest Christian traditions.

By teaching, practicing, and displaying calligraphy, communities ensure that language, stories, and sacred texts are passed down across generations.

Calligraphy as Contemporary Art

Today, calligraphy is not confined to religious or traditional settings. It has found its way into contemporary art, street murals, fashion, and digital design. Artists are blending ancient techniques with modern tools to express cultural identity, political messages, and personal narratives.

Some contemporary movements include:

- Calligraffiti: A fusion of calligraphy and graffiti, popularized in the Middle East and Europe.

- Kinetic Calligraphy: Incorporating movement, projection, or video.

- Cross-cultural Projects: Artists combining scripts from different traditions to explore unity and diversity.

These innovations demonstrate that calligraphy is not just a relic of the past but a living, evolving art form that continues to inspire across cultures.

Conclusion: Writing as a Mirror of Culture

Calligraphy is far more than a technique—it is a window into the soul of a culture. Each brushstroke, each curve of the pen, tells a story not only of the writer but of a civilization’s philosophy, values, and worldview. Whether it’s the spiritual devotion of Arabic script, the Zen serenity of Japanese characters, or the rhythmic beauty of Gothic lettering, calligraphy invites us to pause, reflect, and appreciate the art of expression.

In a world increasingly driven by speed and efficiency, calligraphy reminds us of the power of slow, deliberate beauty—of writing not just to communicate, but to connect with something greater.