Exploring Indigenous Food Traditions and Ingredients.

Exploring Indigenous Food Traditions and Ingredients.

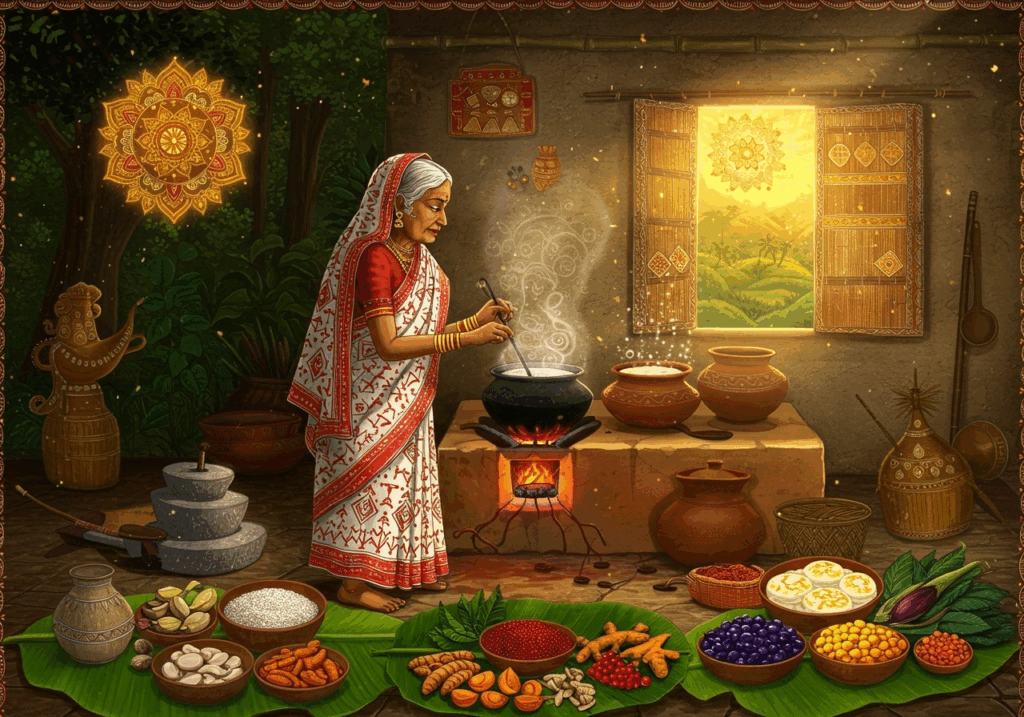

In every corner of the world, indigenous communities have cultivated, harvested, and prepared food in ways that not only sustain life but also reflect deep spiritual, cultural, and ecological connections to the land. These traditional foodways are the original farm-to-table models—built on sustainability, seasonality, and respect for nature.

As global interest in food culture grows, exploring indigenous food traditions offers more than a culinary adventure—it opens a doorway into understanding resilience, heritage, biodiversity, and ancestral knowledge. This blog invites you to journey through the roots of indigenous cuisine, the significance of its ingredients, and how you, as a traveler or conscious eater, can appreciate and support these traditions.

1. What Are Indigenous Food Traditions?

Indigenous food traditions are the culinary practices developed by native peoples based on what the land provides. These traditions vary across geographies and climates but are always deeply connected to ecosystems, cultural identity, and spiritual values.

From the Three Sisters planting of corn, beans, and squash among Native American tribes to the ancient foraging traditions of the Sámi people in northern Europe, indigenous food systems often prioritize:

- Seasonal eating

- Biodiversity

- Natural preservation techniques

- Minimal waste

- Communal and ceremonial sharing

Indigenous cuisines are not only ancient; they are evolving and alive. Despite colonization, land loss, and globalization, many indigenous communities continue to preserve and revive their food practices—blending tradition with modern innovation.

2. The Role of Ingredients: More Than Just Flavor

Indigenous ingredients are central to the identity and survival of native cultures. Often grown, harvested, or hunted with great care and spiritual intention, these ingredients tell stories of resilience and relationship with the land.

a. Maize (Corn)

In many indigenous cultures of the Americas, maize is more than a staple crop—it’s sacred. For the Maya, Aztec, and many Native American tribes, corn is life. From tortillas and tamales to ceremonial uses, maize plays a key cultural and nutritional role.

b. Wild Rice (Manoomin)

For the Ojibwe people in the Great Lakes region, wild rice is a sacred grain with spiritual, ecological, and cultural significance. It’s traditionally harvested by canoe using cedar poles and continues to be a cornerstone of Ojibwe identity.

c. Quinoa

Originally cultivated by the Quechua and Aymara peoples of the Andes, quinoa was once referred to as the “mother grain.” It’s a symbol of indigenous agricultural ingenuity and spiritual significance, now popular worldwide for its health benefits.

d. Kangaroo, Witchetty Grubs, and Bush Tomatoes

Among Australian Aboriginal groups, bush foods—or “bush tucker”—include native plants and animals adapted to the harsh outback environment. These foods are deeply tied to the Dreamtime stories and survival knowledge of the land.

e. Seaweed and Salmon

For coastal indigenous groups like the Tlingit or Haida of the Pacific Northwest, the ocean provides not just sustenance, but a spiritual connection. Salmon, in particular, is revered and used in both ritual and daily life.

These ingredients are grown or gathered using traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), a system that integrates science, observation, and cultural beliefs—allowing communities to live sustainably for generations.

3. Preservation, Cooking, and Sharing: Techniques Rooted in Land

Many indigenous cooking methods reflect a deep knowledge of local conditions and natural resources:

- Pit roasting using hot stones (e.g., Hawaiian imu cooking or Andean pachamanca)

- Smoking and drying fish or meat for winter storage (e.g., Inuit and Pacific Northwest traditions)

- Fermentation and natural curing (e.g., fermented corn dough in Central America or chicha beer)

- Communal feasts and food-sharing ceremonies, such as potlatches or seasonal harvest gatherings

These are not just about nourishment but about community, spirituality, and storytelling. Recipes are passed down orally, often linked to songs, rituals, and cultural identity.

4. Why Indigenous Food Matters Today

In an era marked by climate change, food insecurity, and biodiversity loss, indigenous food systems offer powerful lessons:

- Sustainability: Indigenous farming and foraging practices are models of ecological balance and resource renewal.

- Biodiversity Conservation: Many indigenous groups protect rare plant species and seed varieties essential to planetary health.

- Food Sovereignty: Indigenous movements for food sovereignty empower communities to reclaim their food systems, land rights, and cultural autonomy.

- Cultural Revival: Revitalizing food traditions is often part of larger efforts to heal intergenerational trauma caused by colonization and cultural erasure.

Globally, there’s a growing movement to recognize, honor, and protect indigenous foodways—not only to preserve culture but to inspire more sustainable food futures for all.

5. How Travelers and Eaters Can Respectfully Engage

Exploring indigenous food traditions should come from a place of respect, curiosity, and responsibility. Here’s how you can ethically engage:

a. Support Indigenous-Owned Restaurants and Markets

If you’re traveling, seek out indigenous-run businesses. In places like New Zealand, Canada, the U.S., and Peru, indigenous chefs are bringing traditional cuisine to new audiences while creating jobs and preserving culture.

b. Take Ethical Food Tours or Workshops

Choose tours that are run by indigenous guides or in partnership with local communities. Learn about traditional harvesting, cooking, and the significance behind dishes.

c. Avoid Cultural Appropriation

Cooking indigenous dishes at home? Use it as a learning opportunity. Acknowledge the origins of recipes and ingredients, and when possible, support indigenous growers and authors who share their food stories authentically.

d. Buy Indigenous-Grown Products

Whether it’s wild rice, native cornmeal, or traditional teas, purchasing from indigenous farmers and cooperatives supports food sovereignty and ethical production.

e. Be a Respectful Guest

Food is often part of sacred or ceremonial life. If invited to a traditional meal or event, observe local customs, ask questions respectfully, and remember that you’re being welcomed into a cultural experience, not a spectacle.

6. Spotlight: Indigenous Food Revivals Around the World

– North America: The Indigenous Food Lab (USA)

Chef Sean Sherman (Oglala Lakota), founder of The Sioux Chef, has helped spearhead a Native food renaissance through education, restaurants, and food sovereignty projects.

– Australia: Bush Food Movement

Aboriginal chefs and entrepreneurs are reclaiming native ingredients like wattleseed, quandong, and finger lime—incorporating them into modern cuisine while teaching their cultural significance.

– Latin America: Andean Culinary Heritage

In countries like Peru and Bolivia, native farmers and chefs are revitalizing ancient crops like tarwi (lupin), amaranth, and mashua, while emphasizing their role in nutrition and climate resilience.

– Scandinavia: Sámi Reindeer Culture

The Sámi people of northern Scandinavia maintain traditions of reindeer herding and wild food gathering, with chefs now promoting these ingredients in Nordic fine dining.

7. Conclusion: Honoring the Roots of Cuisine

Indigenous food traditions are not relics of the past—they are vibrant, evolving, and central to the future of sustainable and ethical food. They teach us to eat with intention, honor the land, and value the community around the table.

As travelers and global citizens, we have the opportunity—and responsibility—to uplift and protect these traditions. Whether through mindful dining, conscious consumption, or cultural learning, exploring indigenous foodways deepens our connection to the planet and to each other.

So the next time you savor a bite of food steeped in ancestral knowledge, pause to taste the stories, wisdom, and spirit that make it more than a meal—it’s a living legacy.